https://i0.wp.com/jleshae.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/DSC_0371web.jpg?fit=2000%2C1599&ssl=1

1599

2000

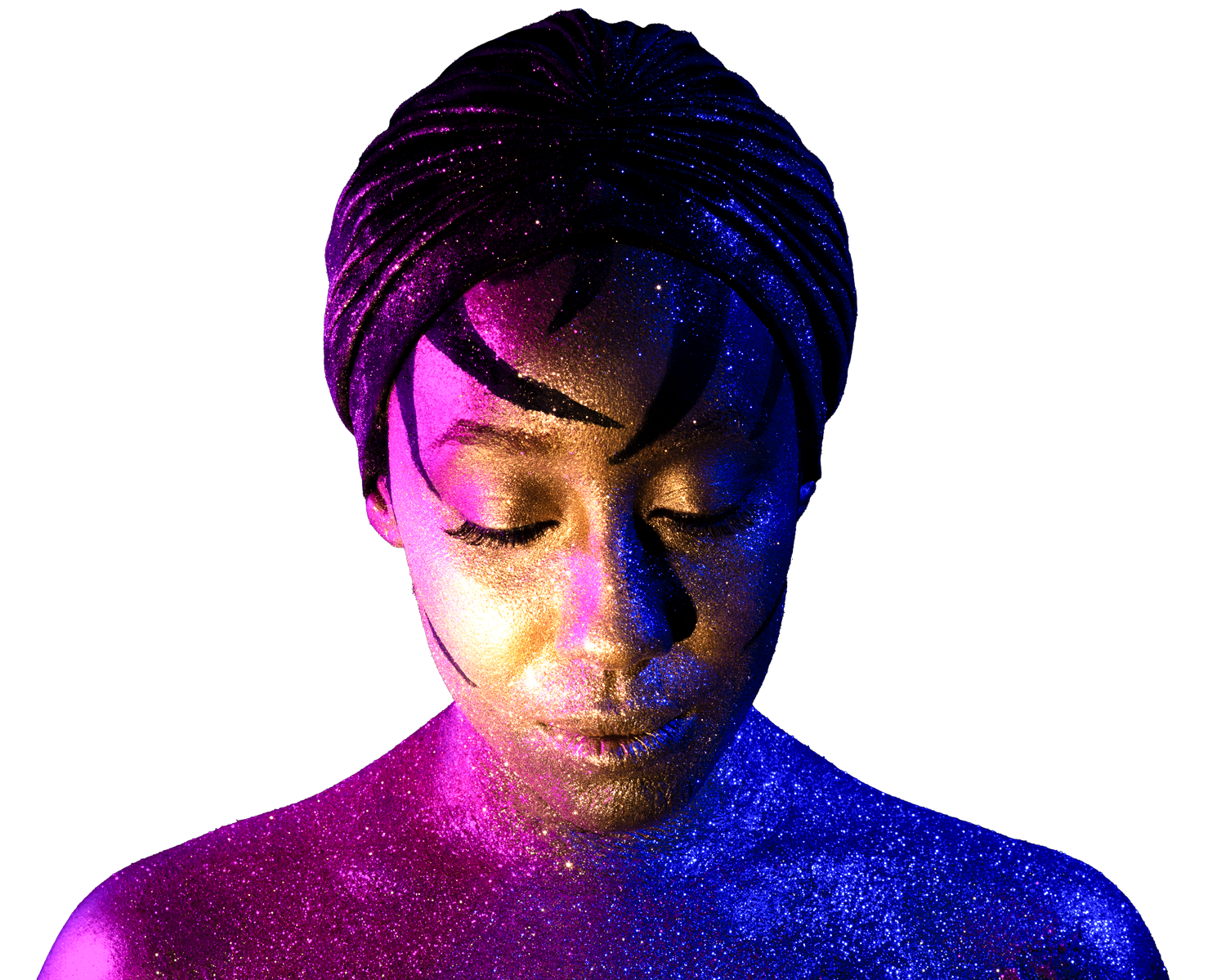

J LeShae

https://jleshae.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SIGNATURE_jleshae_white.png

J LeShae2022-03-31 17:50:262025-02-19 08:04:53May God Protect

https://i0.wp.com/jleshae.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/DSC_0371web.jpg?fit=2000%2C1599&ssl=1

1599

2000

J LeShae

https://jleshae.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/SIGNATURE_jleshae_white.png

J LeShae2022-03-31 17:50:262025-02-19 08:04:53May God ProtectI am here. I am ready.

photography: missy burton

Seven generations ago, my name was Akofena. I was a warrior princess who organized the Ashanti people in battles for our survival and freedom.

At 17, I gave birth to a daughter, Dada, who I loved more than the blood flowing in my veins. She disappeared when she was 10. I didn’t know what to do. I heard stories that she was stolen by ghost people, pale skinned, with no souls. My heart stopped. I lost my will to live. How can a warrior live on protecting entire villages, having failed to protect her own child?

In time, I sought the medicine of our shamans. They taught me to channel the magic of the first mother. In return, I vowed to be reborn and fight with the full force of her vengeance.

I am here. I am ready.

The Texas sun was scorching that August afternoon at White Rock Lake. I was in the center of a field of dry sand-colored grasses posing as Akofena, an Ashanti warrior princess and oldest known ancestor in Missy Burton’s 7-generation Dynasty. The custom crystal-grid pasties that I spent hours constructing didn’t have a fighting chance against the pools of sweat rolling over my body. I tried, repeatedly, to reapply the covers to my breasts, but when they eventually fell face down in the dirt, they were done for. I froze for a split second as a life of insecurity about my tea-cup titties washed over me. Immediately after this, worry of soon-to-come southern conservative critiques about this unladylike activity echoed in my head. But I kept posing anyway, topless.

Something about that moment, embodying an indigenous West African woman, felt familiar… freeing… and I didn’t care anymore. After the shoot, as Missy turned the air conditioning on full blast to cool the car for our ride back to my apartment in Freedman Town, she looked at me with with a mix of excitement and concern. “Are you okay?” I told her I was. Her dark brown eyes burrowed into mine with an unwavering intensity. Unsatisfied with my response, she asked again. “The shots were amazing. It was like you became another person when your pasties came off. Something spiritual happened. But I want to be sure that you are comfortable. Are you absolutely sure that you are ok with me using these photos?” I nodded and explained, “I was okay with it the moment that they fell off and I continued with the shoot.” She smiled. “But, I at least need to give my mama a heads up.” We laughed. I haven’t looked back since.

In a world that fears the womb, and attempts to cage the creatures that carry her, to be a woman assuming full ownership of her body is both terrifying and liberating. And in a world that is especially hyper-sensitive to the Black Female Form, to “consume ourselves,” as artist Classi Nance articulates, is radical. When I review Indigenous African and American herstories, I often wonder about how our ancestors’ perceptions of the world, the woman, and the womb were so vastly different from those of Euro-imperialist-patriarchal traditions. I have so many questions.

Short by J LeShaé for Missy Burton’s Dynasty

Why is it that nature-based and matriarchal cultures were able to peacefully normalize female nudity while capital-based and patriarchal cultures censor and terrorize the bodies of womb-beings? What are the sources of the scars that inspire humans to shackle, silence, and hyper-sexualize womb guardians? What hurt leads humans of all backgrounds to unconsciously believe they have personal rights to the Black Female Form, be it to touch or outlaw her hair, police her freedom of expression, or objectify her being altogether? How did we become disembodied accessories for consumption in sex, science, and surgery?

I don’t know. Maybe I never will, but I will always act upon my rights to center ancestral alignment and ask questions, especially in a colonized world. My life is a journey of discovery and experimentation in the constant pursuit of freedom and liberation. I may endure some pain along the way, but I’ve sewn lots of seeds of love in this lifetime and I expect lots of love will return. Peace will win in the end. No need to shrink or feel ashamed of our independence, imagination, or intelligence. Let’s do what we do and be free.

Raised in a pro-Black artist family in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Missy Burton engages freedom as the editorial lens in her artivist works. She uses photography and a unique technique of color-grading to construct freedom-driven narratives drawn from African/Afro-American folklore and oral histories. Dynasty: A Peculiar Search for Totality is a traveling exhibition that explores the journey of 7 generations of Ashanti women, who, even when forced into captivity, maintained a free state of mind.

Learn more about Missy Burton by visiting missyburton.com or on Instagram @iluv2bmissyb.

photographer: missy burton// hair&wardrobe: j leshaé

READ MORE

Akofena

I am here. I am ready.

photographer: Missy Burton

Seven generations ago, my name was Akofena. I was a warrior princess who organized the Ashanti people in battles for our survival and freedom. At 17, I gave birth to a daughter, Dada, who I loved more than the blood flowing in my veins. She disappeared when she was 10. I didn’t know what to do. I heard stories that she was stolen by ghost people, pale skinned, with no souls. My heart stopped. I lost my will to live. How can a warrior live on protecting entire villages, having failed to protect her own child? In time, I sought the medicine of our shamans. They taught me to channel the magic of the first mother. In return, I vowed to be reborn and fight with the full force of her vengeance. I am here. I am ready.

The Texas sun was scorching that August afternoon at White Rock Lake. I was in the center of a field of dry sand-colored grasses posing as Akofena, an Ashanti warrior princess and oldest known ancestor in Missy Burton’s 7-generation Dynasty. The custom crystal-grid pasties that I spent hours constructing didn’t have a fighting chance against the pools of sweat rolling over my body. I tried, repeatedly, to reapply the covers to my breasts, but when they eventually fell face down in the dirt, they were done for. I froze for a split second as a life of insecurity about my tea-cup titties washed over me. Immediately after this, worry of soon-to-come southern conservative critiques about this unladylike activity echoed in my head. But I kept posing anyway, topless.

Something about that moment, embodying an indigenous West African woman, felt familiar… freeing… and I didn’t care anymore. After the shoot, as Missy turned the air conditioning on full blast to cool the car for our ride back to my apartment in Freedman Town, she looked at me with with a mix of excitement and concern. “Are you okay?” I told her I was. Her dark brown eyes burrowed into mine with an unwavering intensity. Unsatisfied with my response, she asked again. “The shots were amazing. It was like you became another person when your pasties came off. Something spiritual happened. But I want to be sure that you are comfortable. Are you absolutely sure that you are ok with me using these photos?” I nodded and explained, “I was okay with it the moment that they fell off and I continued with the shoot.” She smiled. “But, I at least need to give my mama a heads up.” We laughed. I haven’t looked back since.

freedom & the black female form

In a world that fears the womb, and attempts to cage the creatures that carry her, to be a woman assuming full ownership of her body is both terrifying and liberating. And in a world that is especially hyper-sensitive to the Black Female Form, to “consume ourselves,” as artist Classi Nance articulates, is radical. When I review Indigenous African and American herstories, I often wonder about how our ancestors’ perceptions of the world, the woman, and the womb were so vastly different from those of Euro-imperialist-patriarchal traditions. I have so many questions.

Why is it that nature-based and matriarchal cultures were able to peacefully normalize female nudity while capital-based and patriarchal cultures censor and terrorize the bodies of womb-beings? What are the sources of the scars that inspire humans to shackle, silence, and hyper-sexualize womb guardians? What hurt leads humans of all backgrounds to unconsciously believe they have personal rights to the Black Female Form, be it to touch or outlaw her hair, police her freedom of expression, or objectify her being altogether? How did we become disembodied accessories for consumption in sex, science, and surgery?

videographer: J LeShaé

I don’t know. Maybe I never will, but I will always act upon my rights to center ancestral alignment and ask questions, especially in a colonized world. My life is a journey of discovery and experimentation in the constant pursuit of freedom and liberation. I may endure some pain along the way, but I’ve sewn lots of seeds of love in this lifetime and I expect lots of love will return. Peace will win in the end. No need to shrink or feel ashamed of our independence, imagination, or intelligence. Let’s do what we do and be free.

Raised in a pro-Black artist family in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Missy Burton engages freedom as the editorial lens in her artivist works. She uses photography and a unique technique of color-grading to construct freedom-driven narratives drawn from African/Afro-American folklore and oral histories. Dynasty: A Peculiar Search for Totality is a traveling exhibition that explores the journey of 7 generations of Ashanti women, who, even when forced into captivity, maintained a free state of mind.

Learn more about Missy Burton by visiting missyburton.com or on Instagram @iluv2bmissyb.

invocation: j as akofena//project: dynasty//photographer: missy burton//hair&wardrobe: j leshaé

READ MORE

jleshae.com

jleshae.com

We are IVG. Negro Nose & Afros Flyer. Dallas, Texas. August 23, 2020.

We are IVG. Negro Nose & Afros Flyer. Dallas, Texas. August 23, 2020.

Designer: J LeShae, 2019

Designer: J LeShae, 2019

jleshae.com

jleshae.com

We are IVG. Negro Nose & Afros Flyer. Dallas, Texas. August 23, 2020.

We are IVG. Negro Nose & Afros Flyer. Dallas, Texas. August 23, 2020.

Designer: J LeShae, 2019

Designer: J LeShae, 2019